Two Steps Ahead or Two Steps Behind? Mystery or Suspense?

Two Steps Ahead or Two Steps Behind?

by Amy Maida Wadsworth

Whether you want to write a bona fide mystery with all the genre conventions or are just looking to weave some nail-biting suspense or an air of mystery into your romance or sci-fi, the key to snagging your readers’ interest is in filling them with fear. How you imbue a reader with fear or deep concern requires several strategies, but we’re covering the two primary considerations below. Let’s start with an example:

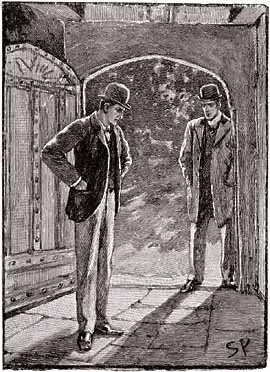

As Sherlock approached 221B Baker Street, he saw splinters of wood where the lock had been jimmied open. He pushed open the door, slowly and silently, to let the dim afternoon light spill through the doorway. Cleaning supplies were strewn across the entryway floor. Someone had forced their way in—a man, who had scuffed his black-soled shoe along the wall on his way up the stairs. He had been dragging someone who snagged her sweater on a protruding nail—the woolen fibers, scratches across the steps where she had dragged the thick heels of her Mary Janes, and the level of fingernail marks along the wallpaper indicated she weighed approximately 120 pounds. Though everything was quiet upstairs, he knew someone held Mrs. Hudson there, likely at gunpoint, and they were waiting for Sherlock’s return. He stepped quietly up the stairs, a can of cleaning spray tucked in his pocket. At least the abductors were imbecilic.*

This is obviously a mystery sample, right? And who better to illustrate the example than Sherlock Holmes? I’ll admit I’m a huge fan. I’ve watched the television show, the documentaries (I recommendHow Sherlock Changed the World), and the movies. I love Sherlock’s focus on detail and power of observation, his knowledge of apparent trivia, and his ability to induce and deduce the truth based on physical evidence. I even love his socially awkward, slightly autistic-savant demeanor. (It doesn’t hurt that Benedict Cumberbatch, in the BBC series, is adorable.)

Sherlock is such a great detective because he’s able to visualize the crime by looking at the crime scene—it’s almost like he stares at the evidence and pushes a rewind button in his mind, then watches the crime occur. This works brilliantly because crime scenes are the physical remnants of crimes, mysteries are the remnants left after suspense is over.

I started this post with Sherlock entering 221B Baker Street after Mrs. Hudson had been snatched. This is what makes it a mystery. I could write it as a suspense scene with a simple shift in point of view.

A scratching at the door interrupted Mrs. Hudson’s cleaning. It wasn’t like Sherlock to forget his key, but he had run out of the house in a start. She stepped into the entryway to make sure. Three burly men forced the door open and rushed to grab her. The tallest of the three slapped Mrs. Hudson with the back of his hand, and she dropped her cleaning supplies, her cheekbone stinging. He grabbed her by the wrists and dragged her backward up the stairs, and no matter how hard she clutched at the wall and kicked at the steps, she couldn’t get away from him. Mrs. Hudson screamed for Sherlock as they neared the top of the stairs. She’d never been treated in such a way—a woman her age, slight of build, respected in the community. What did the men want? What were they capable of if they were so willing to bruise her, beat her, and make her scream? Her heart pounded so vigorously she ached. Perhaps she would have a heart attack. Perhaps that would be best.

There are two main differences between suspense and mystery. One is point of view, the other is time. These differences are important, but suspense and mystery also have a key element in common—fear. Though Sherlock may not seem afraid, he is aware that there is a possibility—however slim—that despite his awesome intellect, he may be too late to save Mrs. Hudson. Mrs. Hudson, of course, is full of fear. Though the levels of fear may differ, it is still the driving emotion in either type of story. As noted above, this fear must be compelling enough that it will transfer to the reader.

Point of View

The biggest difference between suspense and mystery is in point of view. Dwight V. Swain states, “A thing isn’t just significant. It’s significant to somebody.” In other words, events are only significant because they affect people. In the world of fiction, people are more important than events. Feelings are more important than facts. Point of view is the lens that brings events into focus and tells the audience why an event is important.

states, “A thing isn’t just significant. It’s significant to somebody.” In other words, events are only significant because they affect people. In the world of fiction, people are more important than events. Feelings are more important than facts. Point of view is the lens that brings events into focus and tells the audience why an event is important.

Time

If you (as the character or the reader) arrive at a crime scene and the crime has already been committed, you are probably trying to figure out what happened in the past in that crime scene—you are two steps behind, and the novel (or scene) is probably a mystery. You don’t know what happened, and you are trying to figure it out by observing clues—mapping blood spatter, dusting for fingerprints, taking photographs and imagining scenario after scenario—until you can rebuild history in your mind. You feel curiosity and an anxiousness to solve the crime and prevent possible subsequent crimes. Excitement may even accompany your quest as you fit the pieces together and begin to make sense of the puzzle.

If you arrive at a location ten minutes before the crime scene, you will likely be involved in the crime—as a perpetrator, a victim, or a witness—and you’re probably part of a suspense novel. You know what happens because you are part of it. You feel fear, anxiety, and maybe even pain. Panic muddles your thought processes. Your senses are heightened, and your body goes into fight-or-flight mode.

Suspense and mystery happen in the same setting, but from different points of view and at different times. Characters in a suspense novel experience firsthand what becomes the subject of a mystery. Understanding this is important to fulfilling the conventions of each genre and pleasing your genre’s fan base.

Elevating Fear

Since both suspense and mystery require a good dose of fear, it’s a pretty important emotion to portray, and it’s a tricky task. It’s far too easy to feel fear when you imagine a scene but fail miserably in translating it to the page. Part of this is because readers—and writers—have different levels of tolerance and fear (the mere mention of spiders will send some into a tizzy but make others yawn), but mostly it’s because we don’t use point of view and time with enough strategic precision.

To elevate fear, put your point-of-view character in danger of losing something. (It goes without saying that you’ve drawn a compelling character readers care about and thus care if he or she loses something.) This doesn’t mean you’re writing a suspense novel—your detective also has to have something to lose if he doesn’t solve the case. Even emotionally aloof Sherlock will lose the game of being unstumpable if he can’t solve the mystery at hand. Loss equals danger, and danger equals fear. The greater the sense of loss, the greater the fear.

Another way to elevate fear is to shorten the amount of available time. If you put time pressure on your character, you again increase the odds of loss and increase the amount of fear.

Do This Now

- Since this article focuses on point of view in developing reader interest, be sure to review our article about point of view, and check out those action steps as well.

- Listen to a podcast that sparks your imagination about time, memory, and what it means to try to figure out the past. I love the podcast Serial, a popular spin-off of This American Life. The first season of the podcast explores a real-life murder and the guilt or innocence of the young man convicted of the crime. Another podcast that sparks my imagination every time I listen to it (by the same producers) is The House on Loon Lake.

- Once you’ve heard The House on Loon Lake, do some family history. Seems like a strange action step, but family history is an act of restructuring the past, and solving mysteries about family traditions, quirks, and the meaning of heirlooms. You can build a story in any genre around an object with memories attached. Remember, suspense stories create the clues that mysteries interpret.

- Fan fiction is a great way to practice your writing skills, and it makes for a fun writing group session. Choose your favorite scene from your favorite mystery and rewrite the scene from the point of view of the villain, the victim, or a witness, then make that scene part of a suspense novel. Or do it the other way around. Choose your favorite suspense novel and turn a scene into a mystery.

- Share your fear. As already discussed, fear is a tricky but important emotion to incorporate in your writing. Strengthen your fear-writing skills by sharing your fears. Start this process by describing a fearful experience or a nightmare without ever using the word fear. Use your senses in this description. Be aware that when you are in the throes of fear, time shifts—it either slows down and you are painfully aware of everything you experience, or it speeds up and blurs into an indecipherable haze. This depends on your character’s mental state and how he reacts to what happens to him. It depends on point of view.

- Check out How to Write Killer Fiction: The Funhouse of Mystery and the Roller Coaster of Suspense

.

* Summarized from “A Scandal in Belgravia,” an episode in season 2 of BBC’s Sherlock.

Amy Maida Wadsworth published three novels with Covenant Communications—Shadow of Doubt,

Amy Maida Wadsworth published three novels with Covenant Communications—Shadow of Doubt,

YOUR TURN: If you found this information helpful, please share! And now your thoughts—which mystery writer or mystery-writing tactic have you found the most helpful for building reader suspense?

Want to see more helpful writing tips? Check out http://www.eschlerediting.com/

Comments